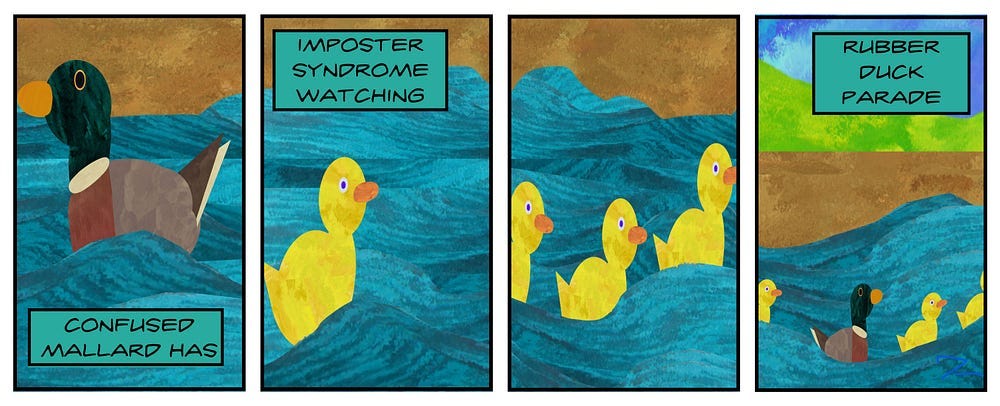

Embracing Imposter Syndrome

Learning to incorporate imposter syndrome into my creative practice

Hello, Creative Friends!

Below is an article that originally appeared in The Writing Cooperative. I’ve tweaked it a bit for my newsletter.

In addition to being a poet, illustrator, and essayist, I’m also a copywriter specializing in working with authors, artists, and creative businesses. I write book sales descriptions (blurbs), About pages, and other sales copy. If you’re interested in working with me send me an email. You can always visit my website to learn more about my copywriting work.

Embracing Imposter Syndrome

Twelve years ago, I left the ashes of my law career behind and, out of desperation, tried to become a writer. After multiple late-night Google searches and countless how-to-make-money-online blog posts and forum threads, I decided I would take a crack at being a copywriter.

While I had slight misgivings about this new career move, I needed cash and didn’t see any other options. I did one of my patented ready-fire-aim maneuvers and started writing for content mills, searching job boards, and signing up for every freelancing platform I could find.

Ever since high school, my teachers and professors had praised my writing. I had read what was already being published on the web, and all of this gave me an unearned confidence that I could figure out copywriting on my own.

Notice what I didn’t have when I was a new, inexperienced, ignorant writer? Imposter syndrome.

I didn’t know enough to doubt my skills.

In the early weeks, I met with some success. I made some much-needed cash. But the writing for pennies was killing me. I was working brutal hours, and I knew this was not sustainable because, in addition to building a new freelance writing business from scratch, I was the primary caretaker of four children—all under the age of eight.

I realized I needed more skills and knowledge about the industry to make better money.

It was only after I had read a dozen books and taken an excellent, but pricey, copywriting course that I began to truly see the full scope of the opportunity before me.

I stopped writing for content mills and taking $5 for 500-word blog post writing jobs and graduated to first ten cents per word, then twenty cents per word work. I gradually increased my prices as I leveled up my skills and confidence.

During this time, I first experienced imposter syndrome as a writer. I was familiar with this creature, as it had haunted me for my entire nine-year legal career. But the form it took with me as a writer was different.

I let it stop me from starting some projects. I let it talk me into quitting a few projects midway through, because I knew I wasn’t good enough to bring them to completion.

I tossed out a novel rough draft because it was garbage. I stopped writing personal essays because, let’s face it, I was never going to be David Sedaris.

Imposter syndrome only showed up for me when I was skilled enough and knowledgeable enough to know what good writing was and when I was in a place where I cared enough about the quality of my work.

When writing for a penny a word, I didn’t care about the quality of the piece I was working on. I just needed to get it done so that I could work on the next piece coming down the assembly line.

Once I was making enough money to take my time on a piece and to consider how it fit into the client’s marketing strategy, I started to worry that I wasn’t good enough—that since I had no formal writing, marketing, or advertising degree or training, I was a fraud.

Imposter syndrome started affecting my ability to earn a living as a working writer and to keep me from growing. Pitch a literary magazine? No way, I’m just a copywriter. Pitch a dream copywriting client? No way. I’m just a self-taught hack who has no business in the copywriting world.

I might write haiku poetry for myself—but would I ever submit it to a journal or publish it for the world to see? No way.

Imposter syndrome is just one of the many faces of fear.

I like to personify the different parts of my brain and personality to help me deal with my tendencies toward panic and self-sabotage.

Fear is a primeval character existing in our brains to keep us safe. Fear asks us to check twice (or thrice) before taking any risks. This can be a good thing. If you’re thinking about jumping off a bridge into a river below for thrills and to show off for a potential paramour, you should think again.

But fear is not a good leader. Maybe I’ve seen too many movies, but I like to imagine life is one big heist. It’s a long con where you try to convince others you know what you’re doing as you slip past the unwary gatekeepers to steal unearned glory and treasure. Fear will get you busted every time.

Whether you like it or not, fear is part of the team. If you’re a writer or any other kind of professional, you’re stuck with imposter syndrome. Once imposter syndrome arrives on the scene, there is no way to get rid of them completely.

You cannot write fast enough to get away from imposter syndrome. What you can do is keep imposter syndrome from running the show. You need to give imposter syndrome a different job.

Imposter syndrome is your lookout

Every good heist team requires numerous roles. You need a leader, hacker, influencer, wheelman, and you need a lookout.

Because imposter syndrome is just another face of fear, it’s perfect for spotting danger. However, imposter syndrome cannot be allowed to decide what to do about that danger. That is the leader’s job.

When my imposter syndrome starts to freak out about not having the right skills, or about being in over my head I like to talk to it, out loud. I always address it by its true name.

“Thank you, Fear, for warning me of danger. You have done your job. I understand that writing this piece is a risk, but we have the skills to get this done. I need you to keep on the lookout for other dangers now while I finish this draft.”

The funny thing is that it works. My nervous system calms down. Fear stops jumping up and down, trying to get my attention because I have acknowledged it.

I first learned this approach from Elizabeth Gilbert’s book, Big Magic, and adapted it to fit my mental model and propensity for seeing the world as some kind of Elmore Leonard novel.

How imposter syndrome evolves with you

One reason it’s a fool’s errand to try and eliminate imposter syndrome is because it morphs and evolves as you grow as a writer. Author Stephen Pressfield sees imposter syndrome as a manifestation of Resistance, the enemy of every artist. It’s like matter and energy—something that has always existed, and that can neither be created nor destroyed. You can only temporarily defeat it by doing the work.

I’ve found that imposter syndrome started as a nagging voice when I was a newer writer, telling me I was uncouth and unschooled. Its tone changed when I was in the journeyman phase of my career.

Imposter syndrome tried to keep me from developing my artistic voice by tempting me to play comparison games. You may have seen the signs of this when I mentioned I stopped writing personal essays because I knew I’d never be David Sedaris, my personal essay idol.

My early efforts were very much poor imitations of Sedaris’s sardonic style. However, when I felt the call to return to personal essay writing and told my imposter syndrome to cool it and look for something else to worry about, I gradually developed my own creative non-fiction voice.

In the end, when we listen to imposter syndrome, it’s right.

You are not as good as whoever you are comparing yourself to because you are not them. There is no competition. I’m a horrible David Sedaris, but I’m not a half-bad Jason McBride.

During the pandemic, I became an illustrator and experienced the different stages of imposter syndrome all over again. I had learned how to write through my fears, but creating visual art was different—or so I thought.

It took me several years to see that my style as an illustrator is influenced by other artists, but it’s also formed by my strengths and weaknesses as a writer. That doesn’t mean I shouldn’t ever publish my illustrations or pitch my skills to clients and media outlets. My illustrations, like my writing, are about more than my skills. They are about the way I see the world.

I can always get better, so long as I keep working and publishing.

More importantly, my words and pictures mean something to some people. When I hide, when I refuse to do the work I’m called to do, I’m not only stalling my growth as an artist, I’m robbing a handful of people of an experience that they find moving.

Giving into imposter syndrome is a selfish act that, like all selfish acts, hurts others at least as much as it hurts yourself.

Imposter syndrome can make you a better writer

Lots of advice about imposter syndrome is about ignoring it or sidelining it. You can read Gilbert’s and my advice to speak to your fears as a method for sidelining imposter syndrome.

But that’s not what it is. It is listening to your fears and actively acknowledging that imposter syndrome has something valuable to tell you while not letting it lead your creative process.

Imposter syndrome is part of your creative process. It does have some important things to tell you, things that can make you a better writer.

I’ve been a working writer for more than twelve years. Some years have been better than others, with the past year bringing many new challenges.

I noticed recently that imposter syndrome was squawking again. I tried to tell it to keep it down because I had work to do. But that stopped being effective. It stopped working because I wasn’t listening to what it said.

My imposter syndrome was telling me that the quality of my work was uneven. I was getting worse. In this case, it was right. I was playing it safe, and my heart was not in the work I was doing.

I needed to pursue clients who were a better fit for my voice and values and pitch media outlets with the stories rattling around in my brain.

My dialogue with imposter syndrome had changed from the gentle, “I hear you, but…” to “Right. Now, sit down and let me cook.”

Once I tuned in again to what imposter syndrome was saying, our dialogue changed to something else.

“Thank you, Fear, for warning me of danger. I’m unsure if this piece is good enough, but now is not the right time to worry about that. This is just a draft. I need you to sit down and keep watching. When this draft is done and it’s time to edit, I will listen to what you have to say.”

I noticed that my fears were keeping me from getting into the flow of my work. When I write without flow, my writing is stilted, lifeless, and without soul. Once I promised to listen to fear during the editing, it was easier to find flow again.

I do keep my promises. Now, after I finish a draft, I let it sit, and when I start editing, I question fear about what problems it sees with my draft.

Remember, I don’t let fear lead. It’s the lookout. Much of what it worries about is not worth worrying about, but it’s great at spotting cliches and helping me properly source quotes and information.

Fear is even a decent guide to deciding where to pitch my work.

I do not like experiencing fear under the guise of imposter syndrome, but my work is too important to my health to let it stop me.

We now have a decent compromise. Imposter syndrome is heard and part of my creative process, but it mostly stays out of the way during the critical ideation and rough draft phases.

I’ve embraced imposter syndrome as inevitable and ever-present. I just don’t let it make any of the creative decisions.

I know a paid subscription is not an option for everyone. If you enjoyed this post and want to give me a tip instead of committing to a paid subscription, you can do that here:

Thank you for reading and sharing my work

Be the weird you want to see in the world!

Cheers,

You're welcome, Jason. In my opinion, those who never feel impostor syndrome are either unaware of it or are trying to mask it cleverly. I'm glad you like my paintings. Have you seen my latest post?

imposters as enemy of the quest to establish own voice and all that. which for me was a constant threat. getting the writer to yes. gave up arguing with its need to explore free writing methods, gave up arguing with its need to rhyme, there is something about getting out of your own way, that destructuring the wanna bee, unquestionably provides.