How the Practice of Haiku Can Help Keep You Resist Tyranny

The philosophy of of haiku goes beyond counting syllables

Hello Friends!

We live in dangerous times. Enough political analysts and journalists are detailing the unfolding events that I would not be helpful joining in.

However, I do believe there is a place for each of us in fighting against authoritarianism. Today’s essay is focused on how to use the discipline of writing haiku as a way to keep yourself safe and as a method for resisting tyranny.

An Ancient Japanese Practice That Can Help You Resist Tyranny

It’s impossible to get on any social media app and not be flooded with notifications about horrible events. Violent forces are increasingly targeting marginalized groups and their allies. And while it is true that social media algorithms tend to reward content that sparks rage and despair — it’s also true that the world is a more dangerous place right now than it has been for a generation.

Many people feel they have two choices: submerge themselves in the torrent of breaking news or bury their heads in the sand and ignore what is happening.

Neither of these options is good for you. Neither of these things will help keep you and those you care about safe. Fascists would love for you to have either one of these reactions to the events unfolding around the world.

As Ryan Holiday recently noted, we have a moral obligation to be informed, but watching cable news and doomscrolling through breaking news alerts on our phones is not keeping us informed. It is making us sick and limiting our effectiveness as leaders in our communities.

In dangerous times like these, we need to maintain vigilance while also protecting our energy and mental health so that we can take action when appropriate.

Being hopeless makes us helpless.

One ancient Japanese practice that can help you keep your eyes open while also increasing your mindfulness is the discipline of writing haiku.

Haiku is the Poetry of Observation

In English, we often think of haiku as a lighthearted practice of counting syllables — and it can be that. However, the more than 300-year-old practice of haiku can also be much more.

In the Japanese tradition, haiku is the poetry of observation. It is rooted in a rigorous discipline and spiritual practice that frees your mind from anxiety.

When you undertake haiku as a mindfulness practice, when you start to write these short poems in the spirit of the Japanese tradition, you become empowered to engage in the world in a much more thoughtful and powerful way than when you live life running from crisis to crisis.

In Timothy Snider’s essential book, On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century, we learn that one key to resisting authoritarianism is to “Take responsibility for the face of the world.”

He explains that this means that you must notice the signs of hate — and refuse to get used to them. Do not allow them to become just part of the background. Most of us are bad at noticing things.

Part of our human programming is to filter out most of the information we take in and only focus on what is critical for our survival.

You can change what you notice by practicing observation. Writing haiku in the Japanese tradition sharpens your observation skills like few other things will.

In today’s political climate, having a keen sense of observation — noticing subtle changes in the places you go during your everyday routine — is essential.

However, writing haiku does more than simply increase your ability to notice things. It also allows you to connect with the physical world around you. Haiku increases your sense of mindfulness. Mindfulness is not an absence of worry or anxiety.

It is the ability to live in the present moment so that you can deal with what you can control and avoid getting trapped in a downward spiral of despair.

Remember, the enemies of peace and democracy need you to be dispirited to fully execute a takeover of society.

Other Elements of Haiku

In the United States and most other English-speaking countries, school children learn that a haiku is a type of poem with three lines where the first and third lines have five syllables and the second line has seven syllables.

However, there is much more to haiku than that. If you want to get the full mindfulness and alertness benefits from this practice, you need a deeper understanding of what haiku actually is.

In Japanese, a haiku has these elements:

Seventeen syllables split into three parts in a 5–7–5 pattern

Be about nature

Contain a season word

Have a sense of wabi-sabi

Written in the present tense

Be a poem that can be spoken in one breath

The Japanese language and English are quite different, and it’s not possible to write a haiku in English that contains all these elements. English language haiku poets often focus on either the syllable pattern and ignore the one-breath requirement or ignore the syllable pattern and focus on the one-breath requirement.

Also, while Japanese has a canonical set of season words, many English-language haiku poets ignore this requirement because seasons in many places of the world differ from those in Japan.

You should feel free to write haiku in a way that fits your life. The poetry police will not come for you.

However, the closer you can stick to the Japanese tradition, the more useful a haiku writing practice will be in keeping you safe in the turbulent years to come.

Here is my brief guide for getting started writing haiku as a mindfulness practice that also increases your power of observation.

Choose One — free verse or 5–7–5

Because of the structure of English, you cannot write a poem that follows the 5–7–5 pattern and can be read aloud in a single breath.

You must choose to write shorter, free-verse poems that can be read in a single breath or follow the 5–7–5 syllable pattern.

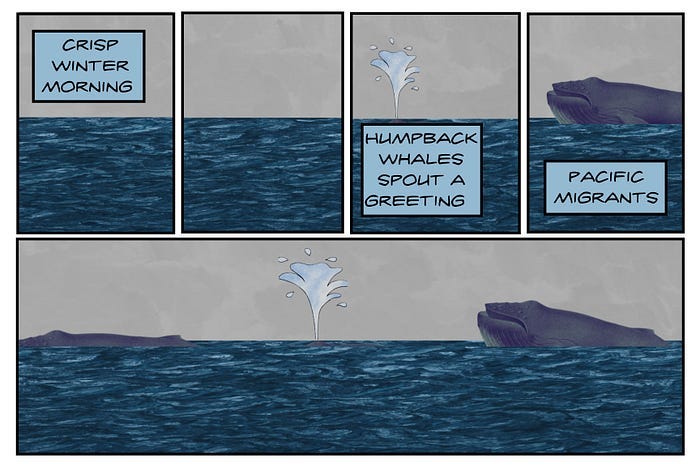

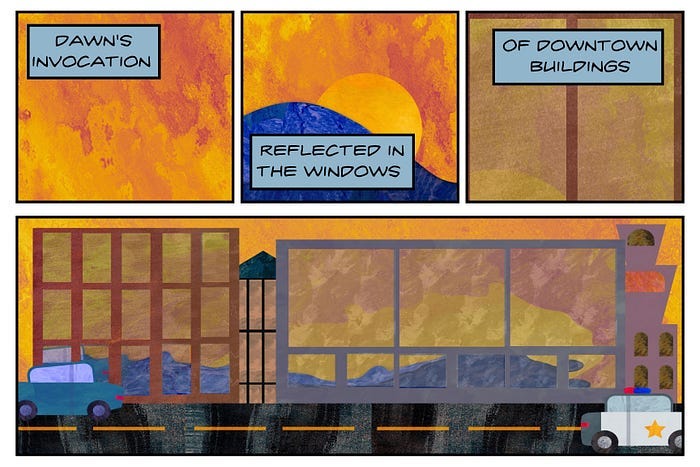

For my practice, I use the 5–7–5 syllable pattern because it is familiar to most English speakers, meaning they immediately recognize my poem as a haiku, and because I love the discipline of forcing my words into the constraint of the 5–7–5 pattern.

There is no wrong choice. I will note that most contemporary literary magazines prefer the free verse approach to haiku. But, I use haiku as a mindfulness practice and am not concerned about literary merit.

Include Elements of Nature

You can write short poems about anything. I’ve written whole collections of haiku about pirates and horror.

However, when seeking to increase your vigilance and connection to your surroundings, it’s best to focus your poems on nature, whatever that means to you.

I consider people to be a part of nature, and I often write haiku about the actions of people, especially how they relate to plants, animals, and the environment.

Writing about what you see the trees or the sky doing tends to have a calming effect on your soul. It also makes it easier for you to notice patterns in the cycles of nature — as well as your neighbors. Writing about nature can help you spot disturbances while there is still time to take action. Writing about the built environment can also provide some of these same benefits.

The key, as always, is for you to experiment and find your own way.

Season Words

I am one of those poets who ignores the canonical season words in haiku because I want to be guided by the climate of where I live, not the climate of Japan. However, I often incorporate signs of the seasons in my haiku.

Like writing about nature, this helps me have a record of the patterns I see. For example, we rarely get snow in the winter where I live, but we often get fog and long rainy days. Gray is a winter-season word for me.

You should experiment with writing haiku to find what you find to be the most satisfying method.

Part of developing a meaningful haiku practice is adapting the principles to your own life.

Wabi Sabi

Wabi-sabi is a Japanese principle that can be difficult to translate. The concept has deep roots in both Shintoism and Zen Buddhism. The core of wabi-sabi is to find beauty in the impermanence and imperfection of life.

Wabi-sabi is not just a concept for haiku. It is found in Japanese art, architecture, and the famous Japanese tea ceremony culture.

Gaining an appreciation for the fleeting nature of life and seeing beauty in what some might consider ugly increases your mindfulness and sense of contentment.

Embracing wabi-sabi gives you the resilience to face life's challenges because it enhances your ability to find wonder and beauty in desperate situations.

Wabi-sabi has been the most challenging element for me to learn. I do not think every poem I write has wabi-sabi, but I work to make it a part of my practice. Looking back on my older work, I find the most comfort in the poems that have captured wabi-sabi. They have a bittersweet feeling to them that I find satisfying.

Present Tense

I often often ignored the practice of writing haiku only in the present tense. However, the longer I work on my haiku practice, the more I’m drawn to writing in the present tense.

For me, the advantages of writing in the present tense are that it keeps me focused on the present moment and makes the poems more dynamic. But, sometimes, using a different tense heightens the emotional resonance of a poem.

You will need to make your own choice here.

Practice Not Perfect

I have written nearly 4,000 haiku since I first undertook haiku writing as a creative practice in 2016. I have written a few good poems, but no great ones.

The point of a haiku practice is not to be perfect — or even to be good at writing poems.

The point of writing haiku is to make you a stronger person, more aware of your surroundings, and more grounded in the present moment.

This is a practice that requires consistency. You will get more benefit from writing one haiku a day or a week than you will from writing ten haiku one day and then not writing another for months.

If you care about resisting tyranny, you must learn to sharpen your senses while maintaining your mental health. You cannot fight authoritarianism when you are hopeless.

Haiku poet and master translate Hiroaki Sato writes in his book On Haiku about ways haiku has been used as protest poetry throughout Japanese history. He also notes how survivors of the atomic blasts that ended World War II used haiku to document their experiences and cope with the horrors of the radioactive aftermath.

The discipline of writing haiku is not some idle literary pursuit. It is a powerful tool to help you survive dangerous times. It is a way to prepare yourself to resist tyranny.

If you enjoyed this post and want to give me a one-time tip instead of committing to a paid subscription, you can do that here:

Thank you for reading! Reading, liking, and sharing this post are great, no-cost ways to support my work and the future of this publication.

Be the weird you want to see in the world!

Cheers,

I really like this point Jason: "haiku is the poetry of observation. It is rooted in a rigorous discipline and spiritual practice that frees your mind from anxiety."

Thank you for this essay, Jason. Please keep banging this drum:

"Remember, the enemies of peace and democracy need you to be dispirited to fully execute a takeover of society."

I need to hear it.