High Lonesome Haiku

Harmonizing the Zen concept of impermanence with traditions of Appalachian bluegrass

Hello, Haiku Fans!

Let’s talk about solitude, impermanence, loneliness, and melding different cultural traditions.

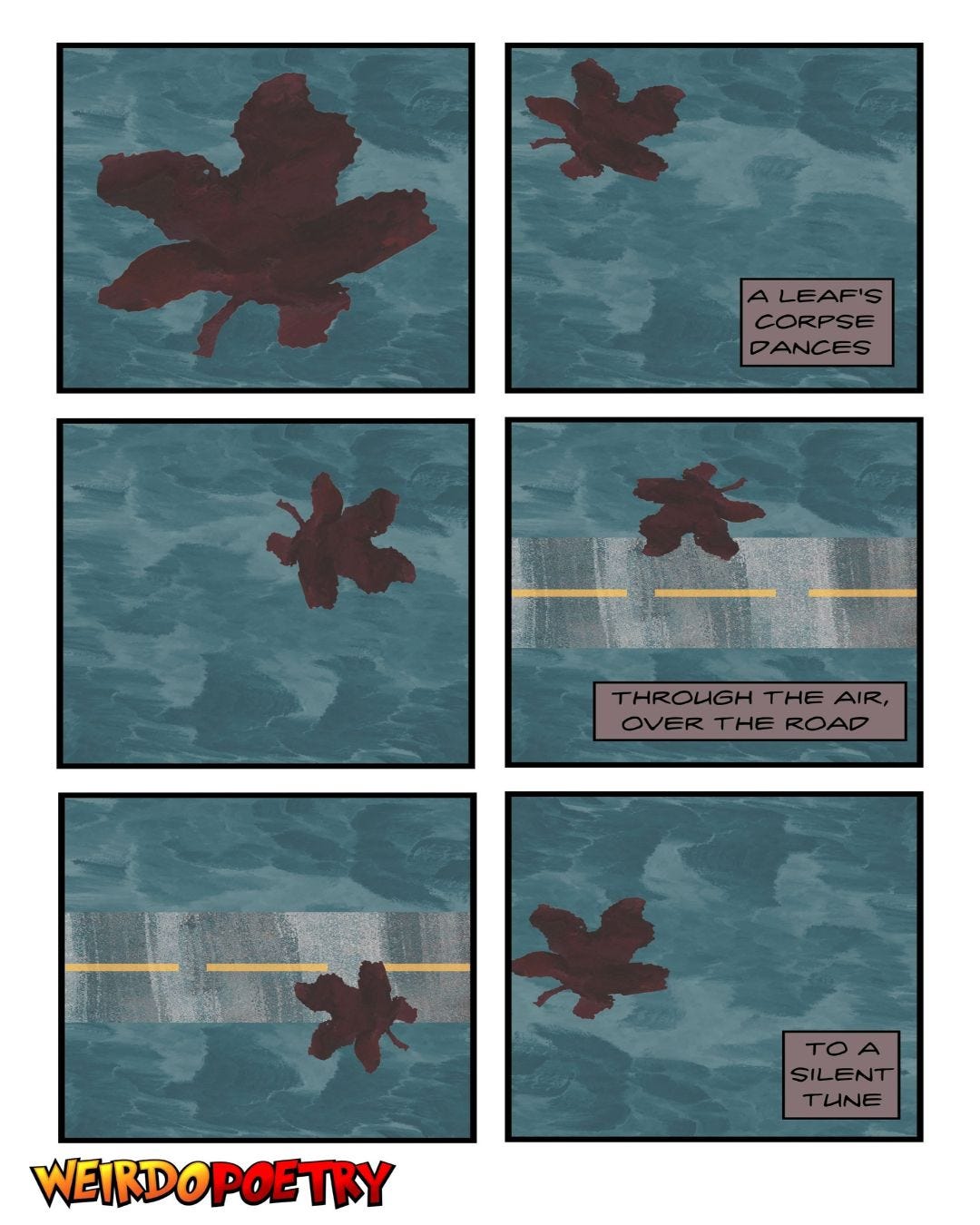

a leaf’s corpse dances

through the air, over the road

to a silent tune

Haiku and the High Lonesome

In traditional Japanese haiku, one of the essential elements is wabi-sabi (侘寂). This term is sometimes found to be untranslatable into English1. In this case, I find the notion of untranslatability to be bullshit.

Wabi-sabi is sometimes described as beauty in imperfection and is a simplification of a beautiful Japanese philosophy and cultural tradition2. However, it’s impossible to talk about wabi-sabi without understanding that this concept has its roots in Zen Buddhism3.

I think a good way to translate wabi-sabi is high lonesome, and I believe it harmonizes well with the concept of high lonesome as formulated in Appalachian bluegrass music in the early 1920s and 1930s, with roots going back to enslaved persons in the American South and several different African musical traditions.

In the Japanese haiku tradition, wabi-sabi means that a poem should communicate the impermanence of everything and celebrate the imperfections found in nature and the manmade as beautiful.

Here is an example of a haiku that embraces this version of wabi-sabi:

our time washed away

like child’s sidewalk chalk picture

in a spring rainstorm

I come at this concept of wabi-sabi from a different angle. I do not speak Japanese. However, I do speak and read Chinese. Japanese uses kanji, a series of Chinese characters as part of its written language. The kanji for wabi-sabi are 侘寂. In Mandarin Chinese, they are pronounced chà-jì.

In Chinese, each character has an individual meaning and its meaning can be altered when combined with different characters, although often it retains its connotations from its solitary form. 侘 (Chà) is usually translated as a boast, but it has an older meaning too, it also means despondent. 寂 ( Jì) means silent, solitary, or sometimes, lonely.

Wabi-sabi has a deeper meaning than as a shorthand for the aesthetic of celebrating imperfections as beauty and remembering the impermanence of all things. This term, going back to its Chinese roots, also means despondent and solitary, or high lonesome.

If you’re not familiar with the term high lonesome, it comes from bluegrass music4. Bluegrass was created in the Appalachian region of the United States. Its form and instrumentation owe a lot to Black musicians. The banjo, a critical component of bluegrass, is an adaption of an African instrument brought to the United States by enslaved people.

Brené Brown writes eloquently about the tradition of the high lonesome in her incredible book, Braving the Wilderness. She adapted a portion of that background in an article for Psychotherapy Networker in 2017. In that article, Brown shares:

Story has it that as a child, Bill Monroe would hide in the woods next to a railroad track in the “long, ole, straight bottom part of Kentucky.” Bill would watch World War I veterans returning home from the war as they walked along the track. The weary soldiers would sometimes let out long hollers—loud, high-pitched, bone-chilling hollers of pain and freedom that cut through the air like the blare of a siren.

Whenever John Hartford, an acclaimed musician and composer, tells this story, he lets out a holler of his own. The minute you hear it, you know it. Oh, that holler. It’s not a spirited yippee or a painful wail, but—something in between. It’s a holler that’s thick with both misery and redemption. A holler that belongs to another place and time. Bill Monroe would eventually become known as the father of bluegrass music. During his legendary career, he often told people that he practiced that holler and “always reckoned that’s where his singing style came from.” Today we call that sound high lonesome.

Wabi-sabi, or chà-jì shares the same sense of the “hollers of pain and freedom” that the bluegrass high lonesome contains. It’s about solitude, despondency, and beauty. It’s bittersweet.

I do not write haiku in Japanese, or even Chinese. I write in English. While I have studied Zen Buddhism in varying degrees of intensity since I was 19, I am not steeped in that tradition the way I am in the American music tradition. To me, the radio was my favorite pastor and many of the songs I’ve heard over that radio, and later my iPhone, are hymns.

When I work at writing formal haiku, poems with the 5-7-5 syllable pattern, season words (kigo, 季語), and wabi-sabi, I am drawing more on the high lonesome sound than I am Zen Buddhism.

This is the beauty of poetry. It allows us to meld different traditions and forge something that speaks to us as poets, readers, and listeners without disrespecting the source traditions.

While I am an optimistic person by nature. I am also subject to long and deep periods of melancholy. I believe that by embracing these periods and allowing myself to feel my feelings of loneliness, sorrow, and grief I am able to release them and move forward on my journey a little less encumbered.

I have found that by allowing myself to sit in sadness, I am better able to accept and hold joy. This is the paradox of the high lonesome.

Below are some examples of my high lonesome haiku. I did not use season words in all of these poems.

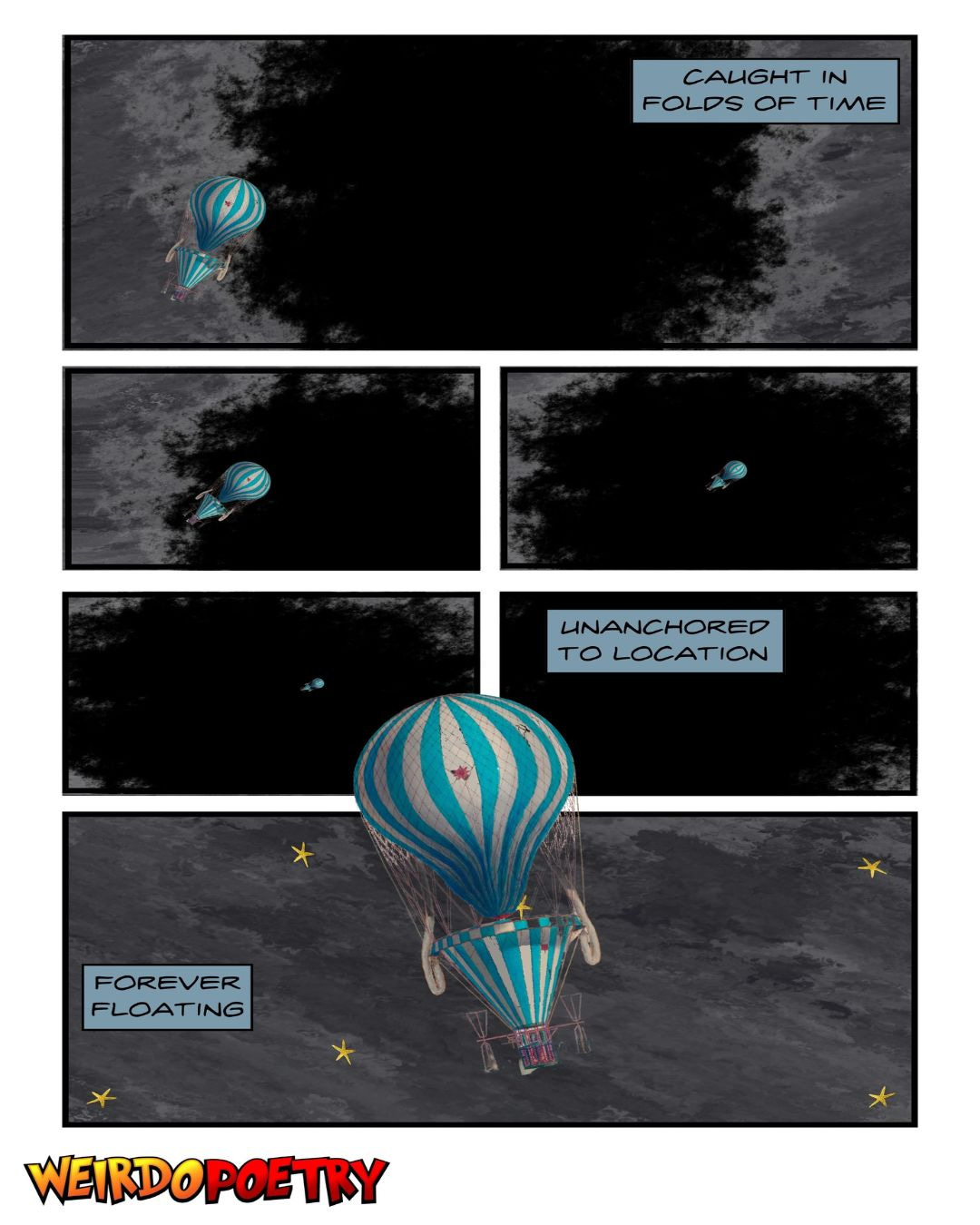

caught in folds of time

unanchored to location

forever floating

the ocean’s sermon

filled with fury, given to

a lone congregant

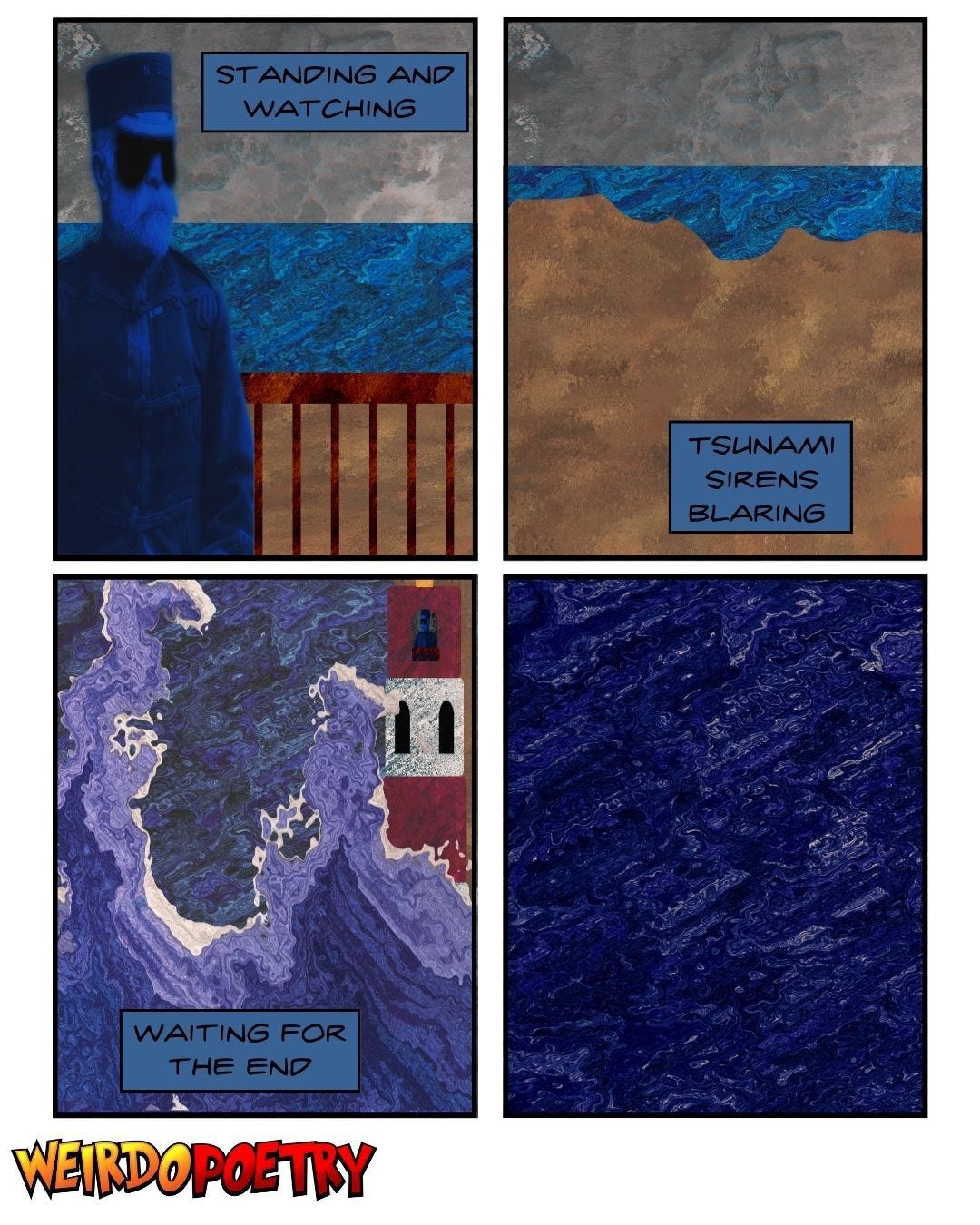

standing and watching

tsunami sirens blaring

waiting for the end

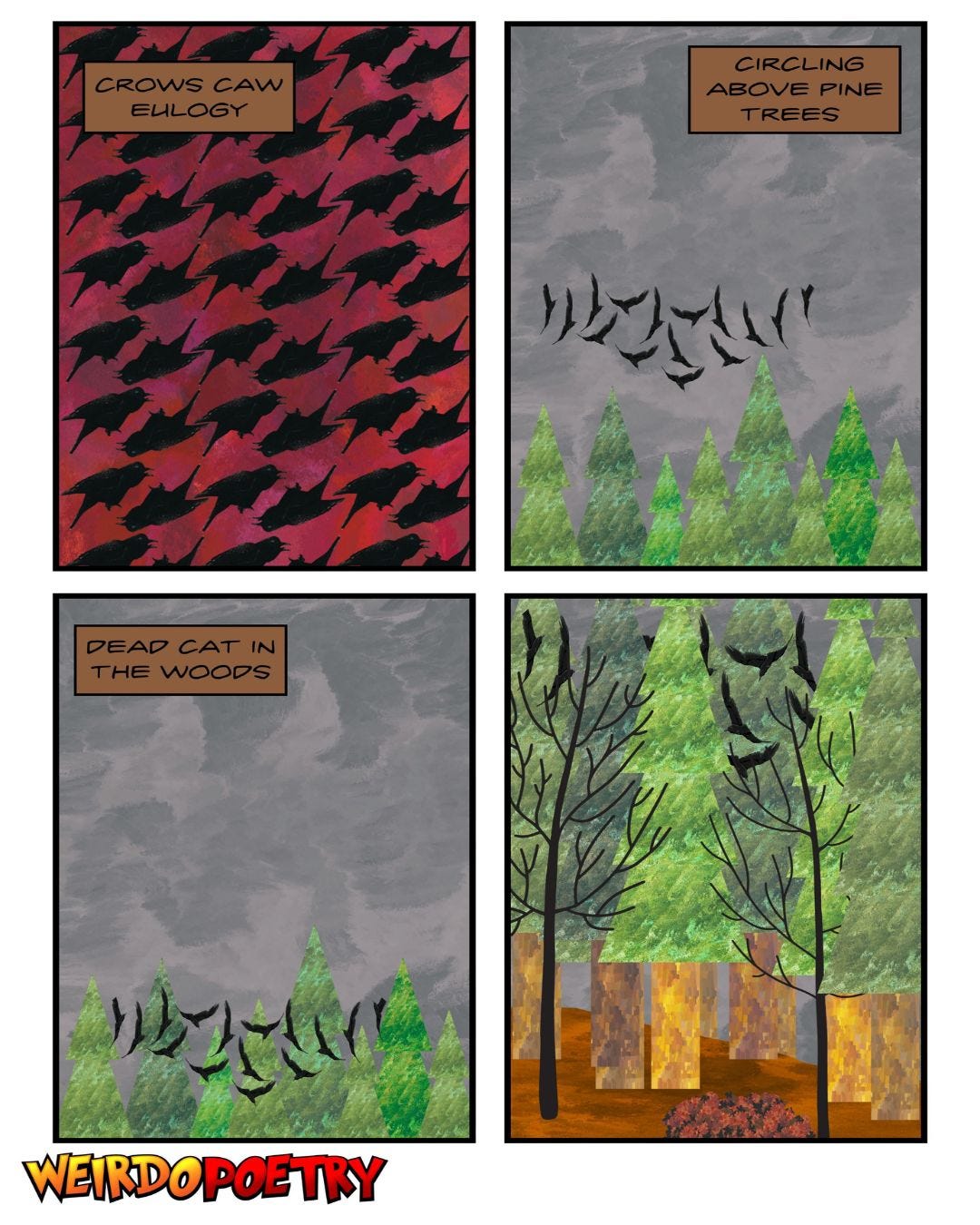

crows caw euology

circling above pine trees

dead cat in the woods

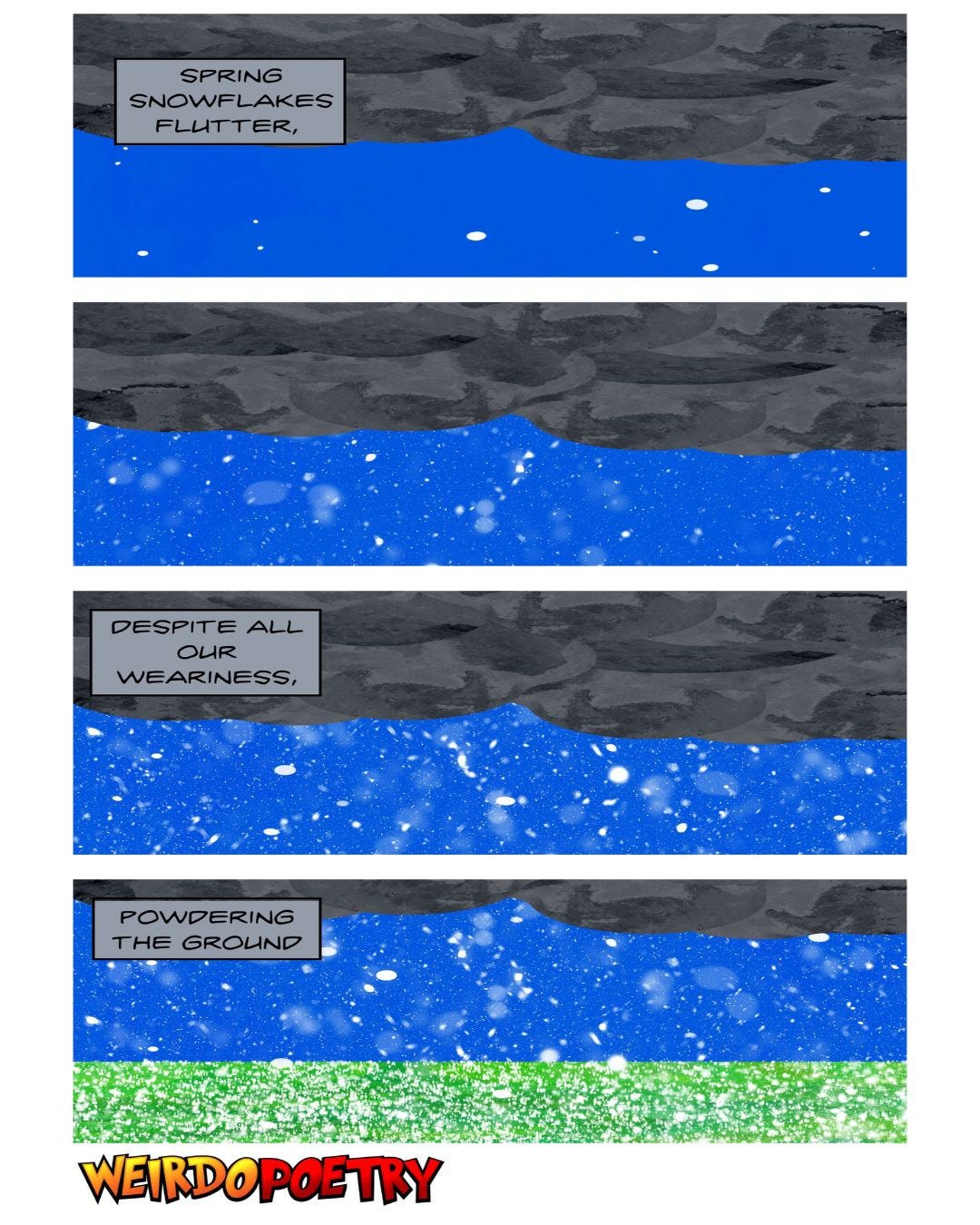

spring snowflakes flutter,

despite all our weariness,

powdering the ground

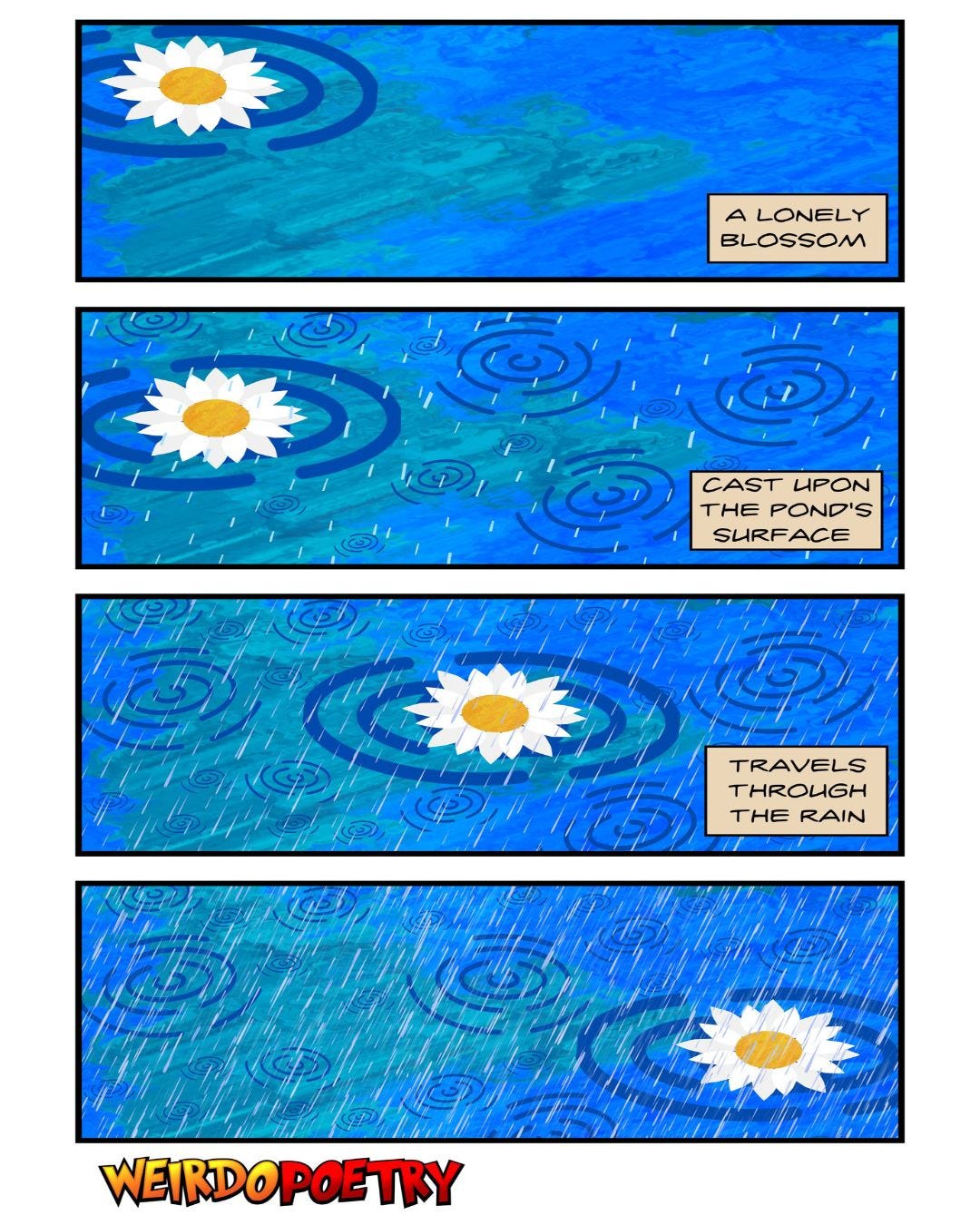

a lonely blossom

cast upon the pond’s surface

travels through the rain

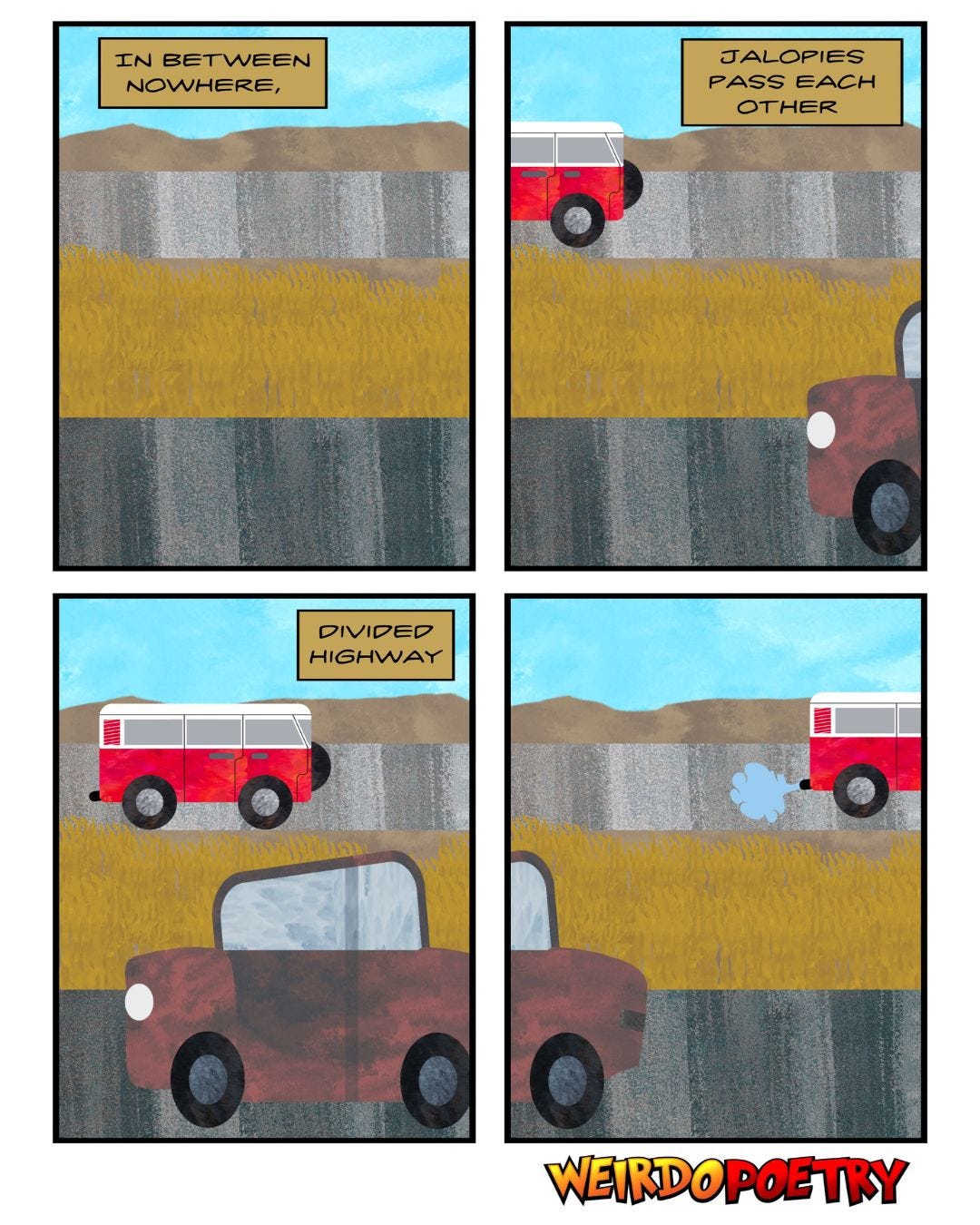

in between nowhere,

jalopies pass each other

divided highway

Haiku Prompt

It’s your turn! Write a haiku, or series of haiku, and use the mood of the high lonesome, or wabi-sabi. Feel free to use the traditional 5-7-5 format or any other format you want.

Please share your poems in the comments! Let’s comfort each other with our poems of the bittersweet.

One last note about the high lonesome sound. This sound, like everything in music, was influenced by something else. It comes from a combination of African, American, and European folk music, blues, jazz, and country and western music (as the genre was called until around the mid-1970s). In turn, bluegrass has influenced every other music genre. Many musical traditions today still carry those high lonesome roots. You can hear clear elements of the bluegrass high lonesome sound in post-1950s country, jazz, blues, and rock music5.

I’ve made a playlist of ten contemporary (within the past ~30 years) songs that capture the mood of how wabi-sabi and the high lonesome feel. I don’t have a fancy Spotify account, but here is a link to this playlist on Apple Music. Below, you will find embedded YouTube versions of each song on the playlist. Try listening to a song or two before writing your haiku.

Wabi-Sabi High Lonesome Playlist

Be the poetry you want to see in the world!

Cheers,

Jason

This article gives an interesting list of Japanese words (including wabi-sabi) that can’t be translated into English but then translated most of them.

This Washington Post article by Richard Harrington gives a lot of great background and history of bluegrass and the high lonesome.

If there is any interest, I will write a follow-up post breaking down the high lonesome in these songs and maybe even write some haiku inspired by each song.

These poems speak to my soul in this phase of life!

His timing was awful

entering at the climax of the film

Oh how I miss him now.