The Real Dangers of Imaginary Creatures

Or the tale of the Pushme-Pullyu and the false binary

Hello, Tamers of Beasts both Real and Imignary!

When facing down the unknown, either you do nothing and accept the status quo or you do something and see what happens. I’m experimenting with audio. In today’s post, you’ll find a clip of me reading the haiku and a separate voiceover for the essay.

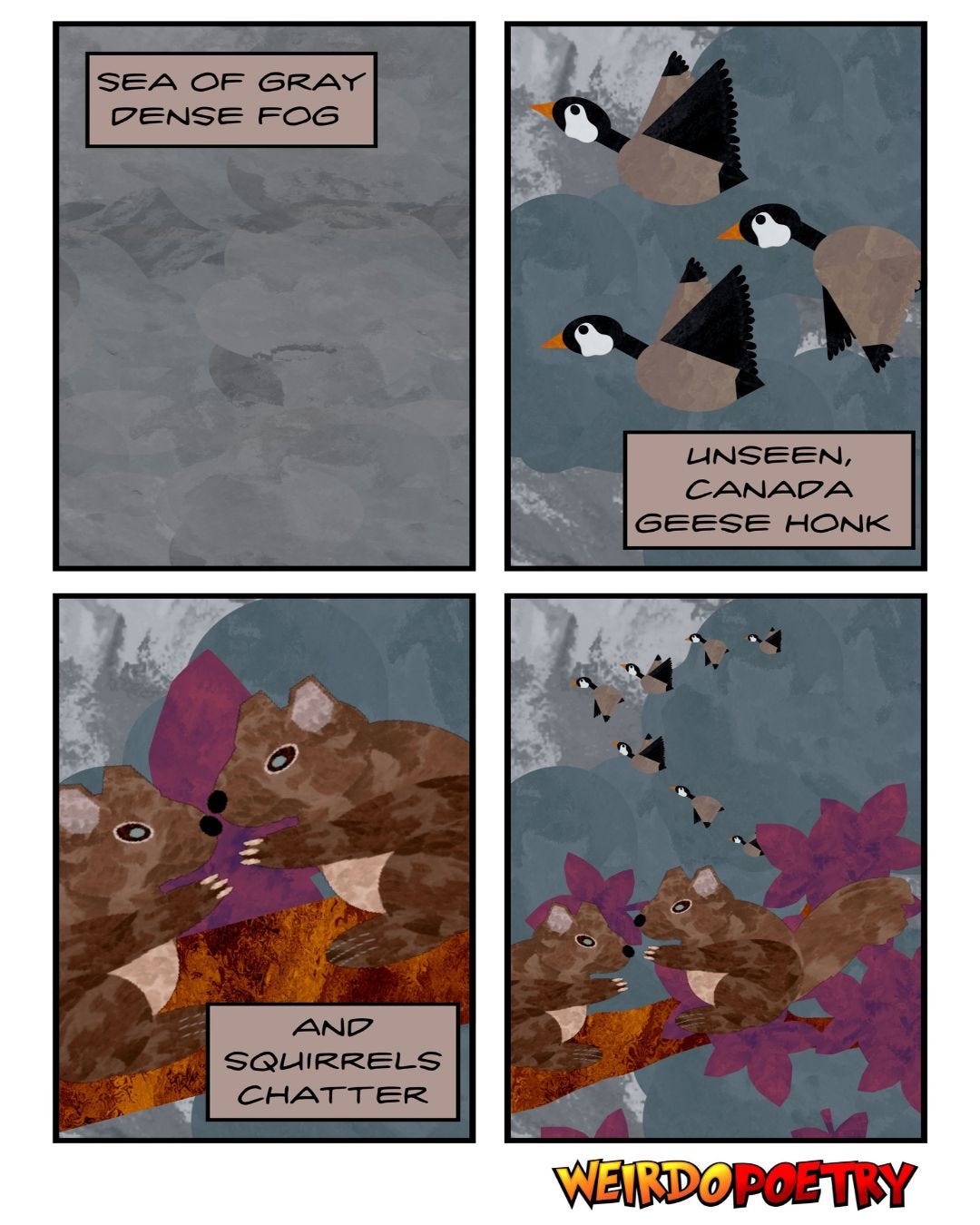

sea of gray dense fog unseen, Canada geese honk and squirrels chatter

The Real Dangers of Imaginary Creatures

My mother was an untreated, undiagnosed schizophrenic. She also had many other mental health challenges. But none of her four children had any understanding of that. She was Mom, and things just were the way they were.

Angels and demons were real for her. Mom would regularly converse with invisible, supernatural beings late into the night.

Later in life, things would get dark for her, and all of us—her conversations would get more fierce and frequent, so much so that Jordan, the youngest, would give her the sobriquet, The Reverend.

Like all of us, Mom contained multitudes. She loved movie musicals and would watch them obsessively. These were the days of VHS tapes. She would buy any musical she could find, and the VCR was the only technology in our home she ever mastered. She would record musicals from the TV and label the tapes in her hasty half-print, half-cursive scrawl.

She would watch the same musical for weeks and months at a time, often until the tape wore out. The movie would play all day while Mom moved in and out of the room muttering and cleaning. Once the movie was over, she would rewind it and start over.

While she watched famous musicals like Sound of Music, West Side Story, Oklahoma, and Singing in the Rain, she also loved more obscure films like the 1967 Rex Harrison vehicle, Doctor Dolittle.

This musical comedy was loosely based on a series of novels by Hugh Lofting and contained three of Lofting’s most interesting mythical beasts, the Great Pink Sea Snail, the Giant Lunar Moth, and the Pushme-Pullyu.

The Pushme-Pullyu was a kind of two-headed llama, that was, for some reason, native to the Tibetan Himalayas.

The Pushme-Pullyu stuck fast in my imagination. I wondered how such a creature would ever survive in the wild, always being of two minds, trying to run in two directions.

Later in life, whenever I would be torn between two choices, I would imagine Rex Harrison1 trying to coax the Pushme-Pullyu up a fork on a steep jungle path. Sometimes, I would label the paths, and the one that Rex Harrison was herding the Pushme-Pullyu towards, would be the choice I would make.

I suppose this was my way of tapping into my intuition.

One drawback that this approach had was that it adopted the idea of a binary set of options. Life is not that simple. Often, we see things as being in conflict and force ourselves to choose one or the other.

Creativity is the ability to resolve these conflicts and create win-win-win action plans. I do believe that often in life we have tradeoffs and constraints. As I once put it:

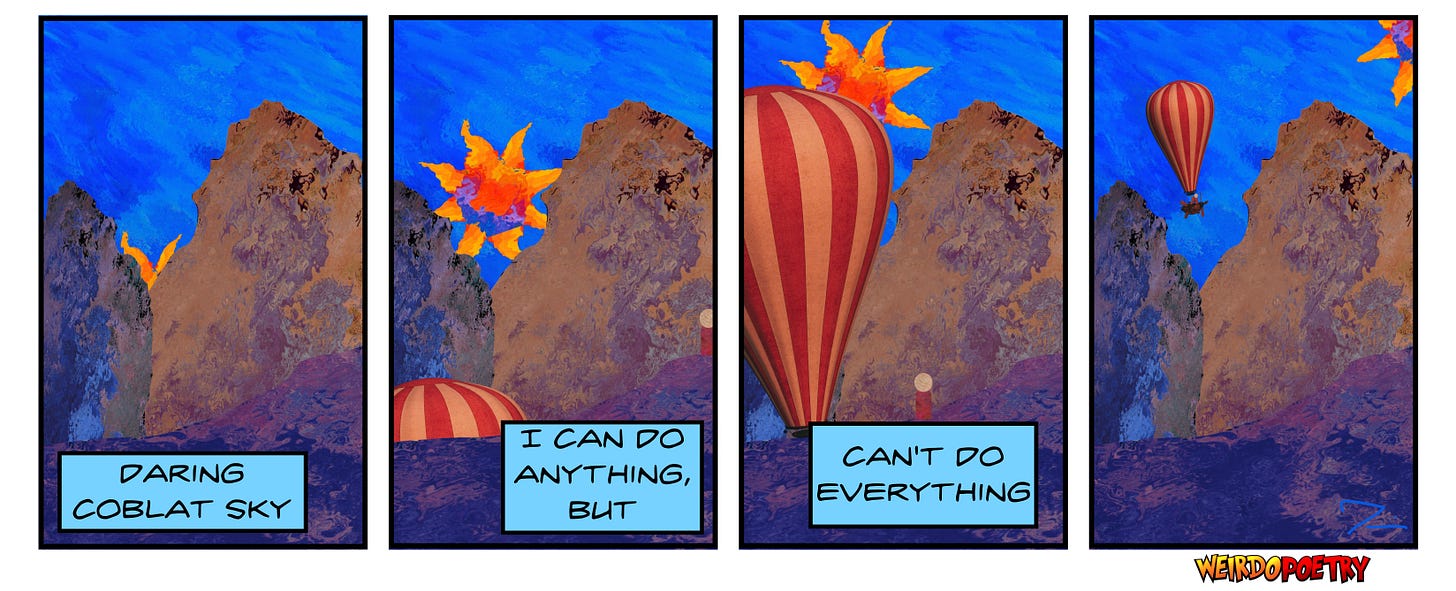

daring cobalt sky I can do anything, but can’t do everything

However, seeing the world as having to choose between the heads of a Pushme-Pullyu leads us to make choices that require us to leave part of ourselves behind. While business schools teach that you must choose between increased profits and increased wages for labor, those tradeoffs are often illusory. With creative effort, you recast the problem and avoid harmful tradeoffs.

Like Mom’s angels and demons, the Pushme-Pullyu is an imaginary creature. When we turn our lives over to imaginary creatures, we are stuck with real consequences.

Creativity is not just for making art. It is fundamentally a skillset and approach to solving problems. Albert Einstein changed physics not because he lived a monastic life devoted to computation and study, but because of his creative way of approaching the problems of physics through his imagination. His was a creative breakthrough.

Many of the technology revolutions of the past fifty years are the work of creative people trying to solve business or technical problems.

Creativity is not about answering questions, it is about knowing that by changing the questions you are asking you will get different answers.

One of the most common false binaries is the one of choosing between art and commerce. It’s based on the notion that art can be good or it can be popular it can’t be both.

Artists are encouraged to think, I can either make art or I can make money. I can do anything, but I can’t do everything.

The temptation is to look and see what work has received the most views or what books have sold the best, and just deliver more of the same.

Push me towards art or pull you towards commerce.

This framework is a lie. Quite often, what resonates, resonates because it is closer to the artist’s inner truth. More of the artist’s soul made it into that piece of work.

If you let metrics like views and sales be the sextant you use to navigate with, you will only travel in a circle, slowly losing readers or fans with each recursive piece of work.

On the other hand, if you ignore what readers enjoy and simply do whatever first pops into your mind, you will end up making self-indulgent work that appeals to an audience of one.

Using creativity, the artist can resolve the seemingly irreconcilable conflict between art and commerce. You can have both art and commerce.

Many have solved this problem. Charles Shultz, the legendary cartoonist behind the Peanuts strips, always described himself as a commercial artist. He was very particular about what his characters did in the confines of his strip, he had a singular artistic vision for Charlie Brown and the gang. Charlie Brown was Shultz’s alter ego. The character was specific and concrete, and because of that specificity, he was universally loved.

The way to resolve the conflict between art and commerce is to discard the binary. There is no Pushme-Pullyu.

Art is the truest expression of the artist’s soul. The more specific you can get in your art, regardless of what your art is, the better chance it will resonate with enough people that you will be able to make enough money to keep making art.

It’s simple—but it’s not easy.

Following the lead of Shultz, I see myself as a commercial poet. That doesn’t mean my poetry is not art.

Being a commercial poet means I am writing to an audience, and I believe that the closer I can get to putting my spiritual fingerprints all over a given piece of work, the more powerfully it will resonate with readers.

I’m less interested in looking clever and more interested in writing what’s true.

While I am not schizophrenic, like Mom, I also converse with the unseen—I just have these conversations through my art.

Come along, if you like and together we can see where these conversations lead.

Be the weird you want to see in the world!

Cheers,

Jason

Rex Harrison is one of those actors that I have a hard time engaging in the suspension of disbelief because every character he plays appears to just be Rex Harrison in a different top hat.

Your essay is brilliant and simple. Your poetry shows the brilliance of simplicity.

You are remarkable